What are

Merchant Services?

Have you ever wondered what, exactly, a “merchant services provider” is? What does a merchant services provider do, and how can working with one benefit your company?

Briefly put, a merchant services provider handles electronic customer payment transactions for merchants. By serving as an intermediary between the merchant’s and customer’s banks, the merchant services provider is able to facilitate the transfer of customer funds to merchant accounts.

Merchant Services, better known as credit card processing, is the handling of electronic payment transactions for merchants. Merchant processing activities involve obtaining sales information from the merchant, receiving authorization for the transaction, collecting funds from the bank which issued the credit card, and sending payment to the merchant.

Back in the good old days, when life was much simpler, “merchant services” was limited to the following scenario:

John Doe walks in to Sam’s Supermarket and makes a purchase. Being that John and Sam were good pals, Sam had no problem extending credit to John. Sam would write down the amount of the purchase in his “little black book” and collect the balance at a later date.

Since this model was driven by Sam’s personal relationship with John, if John were to walk into an unfamiliar store on the other side of town and request credit, he would probably find himself in the uncomfortable position of being shown the front door! Wouldn’t it be great if there were some sort of system that would allow merchants to extend credit to their unfamiliar customers without exposing themselves to risk?

In 1946, the earliest form of “credit cards” (or bank cards) were introduced when John C. Biggins developed a system that did just that. It was known as the “Charg-It” system and it allowed customers to charge their local retail purchases. The merchant then deposited the charges at Biggins’ bank, and the bank reimbursed the merchant for the sale and collected payment from the customer.

American Express is still based on this model to this very day, albeit on a very large scale with millions of merchants and millions of cardholders. Until 2007, Discover also worked this way, but then switched over to the same model as Visa and Mastercard. By 1959, many financial institutions had begun credit programs. Simultaneously, card issuers were offering the added services of “revolving credit.” This gave the cardholder the choice to either pay off their balance or maintain a balance and pay a finance charge.

But this system also had its disadvantages. As more and more banks started instituting their own credit programs, cardholders were presented with the dilemma of walking around with dozens of cards from multiple banks, and merchants were equally troubled with having to deal with many banking organizations.

During the 1960s, the industry took a giant step toward solving this problem by grouping together under one umbrella organization.

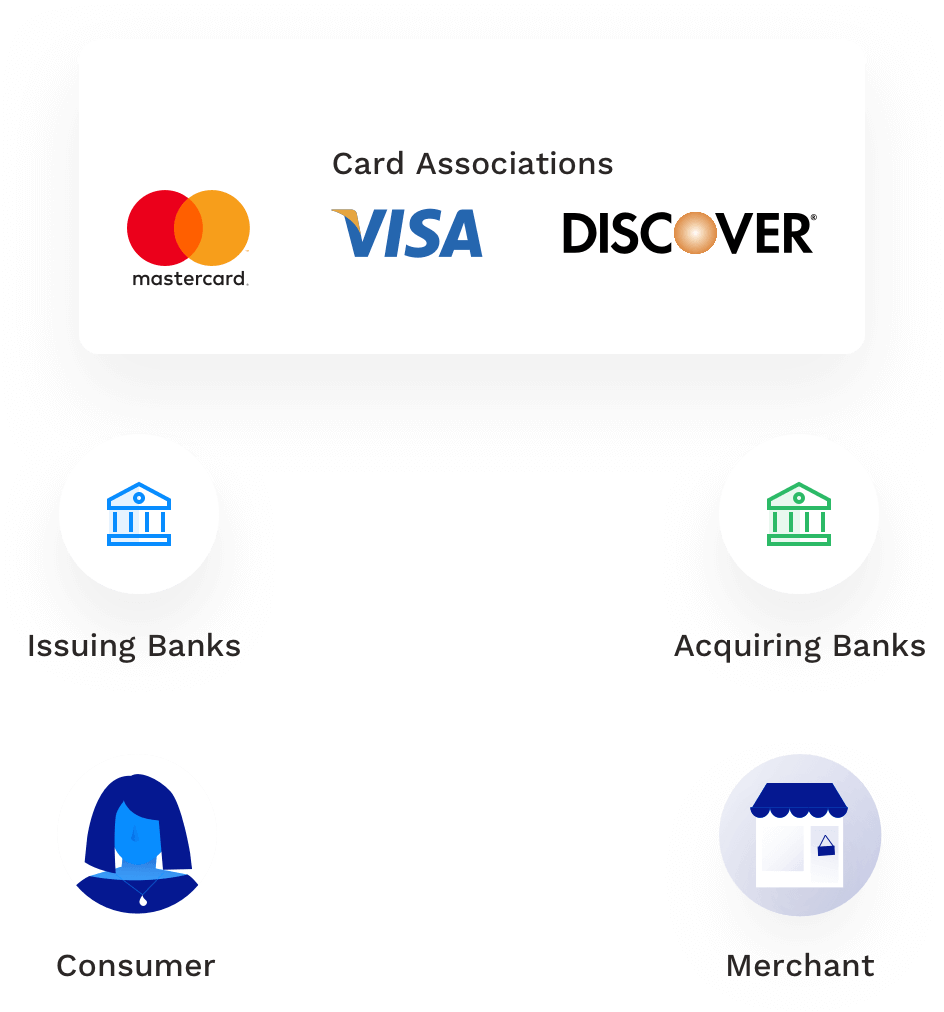

Many banks joined together and formed “card associations,” a new concept with the ability to exchange information of credit card transactions; otherwise known as “interchange.” The associations established rules for authorization, clearing, and settlement, as well as the rates that banks were entitled to charge for each transaction. They also handled marketing, security, and legal aspects of running the organization.

The two most well-known card associations were National BankAmericard Inc., (NBI) and Master Charge, which eventually became Visa and MasterCard (now known as Mastercard).

A big distinction in the new system, as opposed to the old way of doing things was that there are always two banks involved in the process—one on the cardholder side and one on the merchant side—as well as the card associations (Visa and Mastercard) which are not banks, but rather act as the “referee.” The card associations handle marketing, security, and legal issues, but not the actual transfer or responsibility of funds.

The bank representing the cardholder is known as the “issuing” bank, as they issue credit to their customers, and the bank representing the merchant is called an “acquirer,” as they acquire the money on behalf of the merchant. Just as the cardholder must have an account with the issuing bank, the merchant must have an account with an acquiring bank. This account is called a “merchant account” and is used strictly for the transfer of funds from their credit card sales through this account and on to their regular business checking account.

But things were still far from perfect.

During the early 1970s, people were getting weary of the paper-based system. The major problems were losses and huge overhead, not to mention that merchants had to wait up to two weeks for their money. There was a tremendous need for automation and a more cost and time effective way to process transactions. To answer this need, both card associations introduced electronic payment systems in two stages.

The “authorization” system was revamped in 1973. Authorization is the process of guaranteeing there is adequate credit available on the card and capturing that authorized amount to reduce the available credit. This was previously based on a floor limit and a phone call was placed to a call center for any amount over the floor limit. NBI introduced BASE 1 (Bank of America System Engineering 1) which was their electronic online authorization system. That same year Master Charge introduced INAS (Interbank National Authorization System) for “online” authorizations.

In 1974, NBI introduced BASE 2 for online electronic clearing and settlement while Master Charge introduced INET (Interbank Network for Electronic Transfer). Also, in 1974, Bank of America’s international licensees chartered an international company, IBANCO, to administer BankAmericard, Inc., outside the U.S. By the late 1970s, the Interbank Card Association (ICA) had members from as far away as Africa and Australia. To reflect the commitment to international growth, ICA changed its name to Mastercard. Although Visa and Mastercard are two distinct organizations, all banks today are members of both associations. It was not always this way, but in the 1970s they realized that it was to everyone’s benefit to work together.

By 1979, electronic processing was progressing. Dial-up terminals and magnetic stripes on the back of credit cards were introduced thus enabling retailers to swipe the customer’s credit card through the electronic terminal. These terminals were able to access the issuing bank’s cardholder information. This new technology gave authorizations and processed settlement agreements in a matter of one to two minutes. The reduction in paper was an added and much appreciated benefit.

In 2008, Discover joined the interchange model of doing business, and now most acquiring banks offer all major credit cards.

From Purchase to Checkout: The Payment Processing Cycle

From a customer’s perspective, making a purchase using a credit or debit card is a snap—the entire process at the point of sale typically takes just a few seconds from start to finish. But there are actually multiple processes taking place behind the scenes that make a near- instantaneous transaction possible.

Here’s what happens behind the scenes to make it all work.

The Transaction Flow

Step 1: The customer purchases goods or services from the merchant with a credit card; the clerk at the point of sale swipes the credit card through a point-of-sale (POS) terminal or device to obtain the information stored on the customer’s card and then inputs the amount of the transaction.

Step 2: This information is transmitted to the merchant bank (acquiring bank). The information is transmitted in one of the following ways:

- Standard terminal – The sales authorization request is submitted through a standard phone line connection to the acquiring bank.

- IP terminal – The sales authorization request is submitted through an Internet connection to the acquiring bank with a specially designed terminal.

- Processing software – The sales authorization request is submitted through an Internet connection to the acquiring bank using computer software (such as PCCharge Pro) and a small magnetic stripe reader. No traditional terminal is needed.

- Payment processing gateway – The sales authorization request is submitted through an automated Internet website, which communicates with the acquiring bank.

Step 3: The merchant bank captures the transaction and forwards the information to the customer’s card-issuing bank through the bank card association network.

Step 4: The association system then routes the transaction to the issuing bank and requests an approval. The transaction is approved or declined depending on the status of the cardholder’s account.

Step 5: The issuing bank sends back the response. If the transaction is approved, the issuing bank assigns and transmits the authorization code back to the card association.

Step 6: The authorization code is sent from the card association to the acquiring bank.

Step 7: The acquiring bank routes the approval code or response to the merchant’s terminal. Depending on the merchant or transaction type, the merchant’s terminal may print a receipt for the customer to sign (or the customer signs electronically), which obligates the customer to pay the amount approved.

Step 8: The issuing bank bills the customer.

Step 9: The customer pays the bill to the issuing bank.

Settlement of Funds

The actual transfer of funds to the merchant is known as “settlement.” At the end of each day, the merchant generally reviews the days sales, credits and voids. After verifying this, the merchant will close his batch on the POS terminal. This entails closing out the day’s sales and transmitting the information for deposit into the merchant’s bank account (on some terminals and gateways, this might be programmed to happen automatically). The acquiring bank then routes the transaction through the appropriate settlement system against the appropriate card-issuing bank.

The card-issuing bank sends the money back through the settlement system for the amount of the sales draft, less the appropriate “interchange fee,” to the acquiring bank’s account. The acquiring bank then deposits the amount, less the “discount fee,” to the merchant’s bank account. Generally, within 24 to 72 hours, the merchants will have their money. Cutting-edge merchant service providers such as Fidelity offer next-day and same-day funding options.

Important note: Even though a merchant has been funded, the transaction can always be reversed—such as when a customer initiates and wins a chargeback. Therefore, the funds released to a merchant can be theoretically considered by the acquiring banks as a “loan,” which is one of the biggest reasons why the underwriting procedures for setting up a merchant account are so strict.

The settlement procedure differs depending on the merchant’s front-end platform (e.g., Nashville, Omaha, etc.). For example, a restaurant may want to be able to track servers to easily settle tips at the end of the shift. A hotel or car rental agency may want to get a pre-approval before the customer checks in or uses the service. A bar may want to open a tab for its customers. At Fidelity Payment Services, we have many pre-built programs that any merchant can request based upon their type of business.

Interchange (Discount) Fees

Each time a cardholder uses a credit card, the merchant is charged a percentage of each transaction, usually called a discount fee. This fee is charged to a merchant because the issuing and acquiring banks assume all the risks on every transaction (late or no payment, fraud, etc.), yet fund the merchant within 48 hours of the sale. The discount rate is largely comprised of the interchange fee and assessments. Interchange rates are determined by Visa, Mastercard, and Discover. In order for the merchant to receive their funds, the acquiring bank must pay this fee to the issuing bank which is then responsible for releasing the funds from the cardholder’s account. Interchange is the “wholesale cost price.”

All other cards, such as American Express, Diners Club, and JCB (Japan Credit Bureau) set their own discount rates.

The discount fee that a merchant is charged depends on several factors including the following:

Type of business (i.e. industry, brick-and-mortar or e-commerce, etc.)

The merchant’s industry type—such as fast food, colleges, warehouses, gas stations, and more—affects rates. Each transaction must meet one or many factors to qualify for a specific category. Some factors determine if the transaction will be completed, while others determine the rate and transaction fee that will be assessed.

A handful of industries have been assigned a special rate category. In some cases, preferred rates were established to attract merchants to accept credit cards.These include warehouse clubs and supermarkets. In other cases, categorization rules reflect the unique transaction flow for a particular industry; for example, lodging and car rental businesses require authorization at check-in days before a transaction is settled. This means that additional data points like arrival and checkout dates, folio numbers, and length of rental are required to be sent to Visa or Mastercard along with the credit card data. To qualify for these categories, merchants must use industry-specific software or terminal applications, which prompt for the extra information. They must also properly transmit it to Visa or Mastercard.

As a result of new technologies, such as Mobil Speed passes, rates have been created for gas stations, fast food restaurants and convenience stores. Fast food and gas station transactions are normally completed without a signature and are considered more secure than MOTO (mail order telephone order) or Internet transactions, mainly due to the limit set on the amount of each transaction.

Type of card processed (i.e., traditional credit cards, corporate, rewards based, purchasing or check cards)

Visa and Mastercard have created an endless list of names for virtually the same product. The difference between the various commercial cards is defined by the reporting features available to the cardholder.

Commercial cards are designed to help companies maintain control of purchases while reducing the administrative costs associated with authorizing, tracking, paying and reconciling those purchases.The interchange rate for commercial cards is different than the per transaction rate for the average consumer card. In most cases, the interchange cost is higher than the consumers’ rate.

Check cards, offline debit or signature-based debit transactions are routed through the Visa/Mastercard authorization and settlement system. Transactions are settled nightly and authorized by the cardholder’s signature. Due to the decreased risk factor, these transactions are at a lower rate structure. Keep in mind that the money is not loaned; it is money that is already in one’s checking account.

Check card transactions fall into a number of categories. Visa and Mastercard established check card rates that are priced significantly lower than all other consumer credit cards. These new categories provide yet another way for processors to create unique rate offerings.

How a card is processed (i.e., card present or card not present, swiped, dipped, etc.)

Determining what a merchant will be charged is based on the method of card entry and what data is entered. The first and most obvious factor is whether the card is physically present at the POS. Whenever a card is swiped (magnetic stripe) or dipped (EMV chip) through an electronic terminal or card reader, an indicator is transmitted to Visa or Mastercard, along with the rest of the data. It records the fact that the information was received directly from the card’s magnetic stripe. Without this indicator, the transaction is not eligible for any swiped interchange category.

Magnetic stripe and EMV chip technology has been incorporated into more and more products. Readers can be found in computer keyboards, cell phones attachments, and more. Whereas it is relatively easy to capture the information from a magnetic stripe or chip, it is entirely different to properly transmit the information to Visa and Mastercard in a way that will allow the transaction to qualify for a certain rate.

It is possible and, in fact, common for merchants to believe they are qualifying for the best swiped/dipped rates, when in fact their transactions are downgrading, which means higher transaction fees for them. Merchants should be encouraged to test transactions and have their processor verify their qualification levels instead of assuming that a swipe/dip will always qualify for a certain rate.

Note that Visa and Mastercard both make a distinction between a card that was key entered due to a bad magnetic stripe as opposed to a transaction where the cardholder is not present, such as in MOTO or Internet orders. To avoid confusion, merchants should follow one simple rule to ensure that they qualify for either the key entered or the card-not-present rate: Whenever a card is not swiped, enter the information required for Address Verification Service (AVS) as well as an “order number” for every transaction. The order number can be any length.

Additionally, certain categories have strict qualifications, such as merchant category, merchant actions and transaction size. For most categories, the interchange cost is a combination of a percentage rate and a transaction fee.

- Risk presented

- Merchant credit

- Other Factors

Transaction qualification is influenced by many factors. In many cases, the only way to truly know how merchants can minimize interchange costs is to critically examine their bankcard statements.

What is AVS?

In an effort to combat fraud that results from card-not-present transactions, Visa and Mastercard created the Address Verification Service (AVS), which attempts to verify the credit card customer’s address and ZIP code. Whenever a card is key-entered, the processing system should be set up to prompt the merchant to enter the billing ZIP code (for the cardholder’s billing address) and the numerical portion of the cardholder’s address. If this information matches the card issuing bank’s records, the system will qualify that transaction for an AVS rate category. Note that Visa also looks for an invoice number.

To avoid confusion, merchants should follow one simple rule to ensure that they qualify for either the key-entered or the card-not-present rate: whenever a card is not swiped/dipped, enter the information required for AVS as well as an “order number” for every transaction. The order number can be any length.

What is Downgrading?

Transactions are downgraded when they don’t meet interchange requirements, such as not capturing the correct card information at the POS; settling the transaction after a deadline has lapsed; or key-entering rather than swiping/dipping a card. A downgraded transaction means a higher cost for the merchant.

Streamline Your Merchant

Services With Fidelity